Pensions & Divorce

If you are facing the end of your marriage or civil partnership it is important not to overlook pensions.

Pensions and divorce

Divorce is one of the most stressful and painful times people go through. Adding pensions into the mix can be daunting, but not dealing with pensions can be a huge mistake.

People often avoid or overlook pensions because they can seem complicated. Where there is a solicitor involved, they should know to get the pension valued. But where there isn’t, many people, especially women, opt to try to keep the family home without understanding the real value of the share of the pension they have given up. Add in the fact pensions are difficult to value and difficult to divide and we have a complex situation.

Marriage and divorce

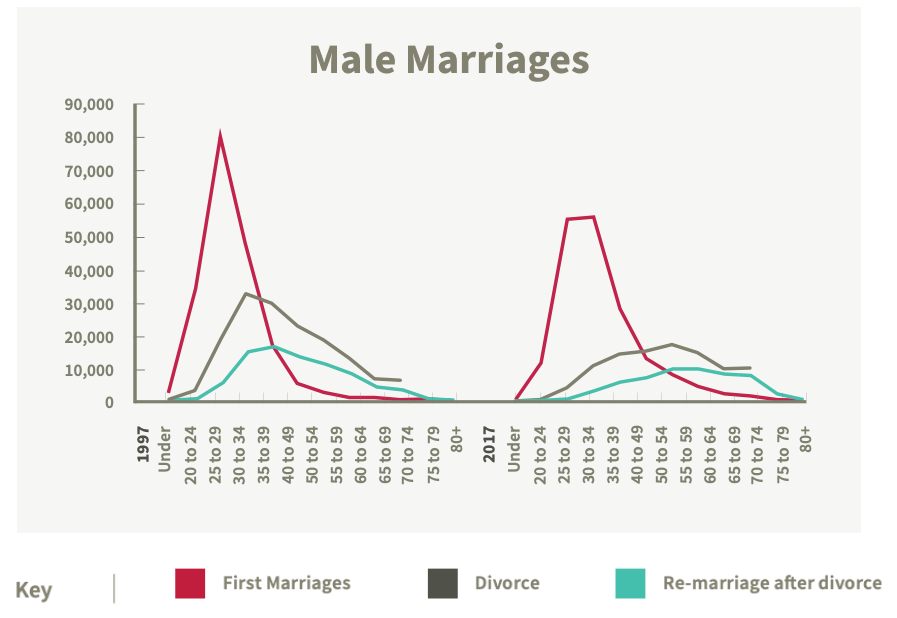

First marriages are less common than they were 20 years ago and now more spread through life.

The average age of first marriage is now 34 among men and 32 among women both four years older than 20 years ago. Divorces are lower and peak twenty years later in life than 20 years ago, including a second peak in the approach to retirement1.

Source: This research was conducted in partnership with Trajectory, a strategic futures consultancy. It uses horizon scanning to identify the key trends shaping retirement now and in the future (to 2035).

Pensions

A person’s pension can be quite substantial, particularly if they have been paying into it over many years.

A pension fund is, for many people, the largest financial investment they will make, and factoring in that many people have a mortgage on their house, then the pension can be the most valuable asset. It is therefore important to consider both parties’ pension provision when trying to reach an equitable settlement. Upon divorce, the non-pension member (the ‘ex-spouse’) may lose the right to death benefits and the right to share in the pension. This can cover the monthly payment which the member receives from their retirement date and the tax-free lump sum which is, normally, available from the scheme.

There are three main ways to take pension provision into account during a divorce settlement. It’s important to note that for options (2) and (3) below a specific court order is required.

3 ways to take pension

First Option (Offsetting)

This has historically been the most popular way of dealing with the pension issue.

Offsetting involves one spouse receiving money or assets to compensate for the loss of pension rights. The pension member will retain their pension fund intact. It may often be used so that one party retains the house, while the other receives assets of an equivalent value (for example the pension and some cash). This means there is a clean break between the two parties which can be beneficial. However, offsetting isn’t always practical or possible.

From the pension provider point of view this is the simplest option as the pension is left untouched. However, there is a risk one individual can reach retirement with little or no pension savings, and that can especially be the case if divorce is relatively near retirement leaving little time to re-build a pension pot of their own. Women are likely to be disproportionately affected by this issue as they often contribute less to their pension for many reasons including time away from work to look after children, or other family members. Women may also be more likely to want to retain the family home if possible as they are generally the primary care giver to children.

Second Option (Pension attachment)

This was introduced from July 1996 and is an agreement the ex-spouse will receive a percentage

of the member’s benefits when the member starts to take them.

This can include the tax-free lump sum, income payments, and death-in-service benefits. In practice the court will specify a certain percentage of benefit is paid to the ex-spouse and, when the member takes their benefits, the scheme will pay the appropriate amount directly to the ex-spouse.

The downsides of attachment orders are the member retains control of the pension asset. The court can’t compel someone to retire at a particular age, so the member decides when to take benefits, and therefore also controls when the ex-spouse starts to receive benefits. In a defined contribution scheme the member also controls the investment strategy, with the ex-spouse having no input. The downside of attachment orders is there is no clean break between the two parties, as the two are financially linked, potentially until one of them dies.

The order may impose certain conditions in the event of a change of circumstances, for example many will cease upon the remarriage of the ex-spouse. As pension attachment was designed well before the advent of the pension freedoms, orders often don’t take into account the flexibility available today and schemes may need to interpret the order while staying within the confines of current pension rules.

Third Option (Pension sharing)

It has been the most popular approach to divide pension benefits since it was introduced in December 2000.

The Court order (known as a pension sharing order or PSO) specifies in percentage terms how the member’s benefits should be split. The share – known as the pension credit - is then transferred to a pension arrangement in the ex-spouse’s own name. This therefore gives a clean break and, perhaps more importantly, the ex-spouse has full control over the investment of the pension and when benefits are taken. Normal pension rules usually apply to in terms of pension age, shape, and choice of benefits etc.

Unfunded public sector pension schemes, as well as some other schemes, give the ex-spouse membership of the scheme in their own right (sometimes called ‘shadow membership’). The rules of the scheme involved will set out what is permitted.

Pension sharing allows a clean break between the two individuals, with the non-member getting a benefit on their own name, under their control. Benefits will be retained in the event of their death or the death of their spouse. Nor will there be a risk if they remarry or cohabit (as is the case with earmarking orders).

A pension sharing order can be placed on a pension already in payment, although this can be more complex. The member would have had the opportunity to take tax-free cash when crystallising benefits and these would have been tested against the lifetime allowance at that point. Therefore, the share given to the ex-spouse is known as a ‘disqualifying pension credit’ and special rules apply.

The ex-spouse may not have reached the minimum pension age and so the benefits they receive are treated as uncrystallised. This allows the ex-spouse to decide when to take benefits. However, the ex-spouse cannot take any tax-free cash when taking benefits (as the member had already received this). That also means an Uncrystallised Funds Pension Lump Sum (UFPLS) isn’t available in respect of these funds. The ex-spouse will be able to apply for a lifetime allowance enhancement factor, as the benefits have already been tested against the lifetime allowance. In simple terms this gives the ex-spouse a higher LTA which can be used for their pension credit, as well as any pension they have built up in their own right.

Not all schemes will accept a disqualifying pension credit (due to the extra complexity/admin) so the ex-spouse will need to check that the scheme they want to transfer to will accept it.

Where there are multiple pensions

Since the advent of automatic enrolment it is even more common that both individuals will have some pension provision.

But it will be rare for that to be equal. Therefore, there will often be a need to get multiple pensions valued. A combination of the above options can also be used. For example, offsetting one pension value against the other to some degree, and then putting in place a pension sharing order to cover the balance. Another example could be an attachment order covering the lump sum death in service benefit and a pension share in respect of the pension income.

Your Basic State Pension cannot be shared, but under the current rules, if one of you has paid enough National Insurance contributions, this could increase the State Pension the other gets providing they don’t remarry or enter a civil partnership before they reach their State Pension age.

If you get divorced or your civil partnership is dissolved the court can decide that your Additional State Pension or the Protected Amount should be shared as part of the financial settlement. But if you remarry then this is lost. You would need to complete form BR20 to give details of your Additional State Pension.

Process

Both parties should engage separate professional divorce solicitors and pension advisers.

Ideally from different firms, to avoid conflicts of interest. They can then help determine who is going to pay for any pension share and how. There can be further complications if the member has some form of lifetime allowance protection.

Parties need clearly to have understood the implications of pension freedoms; complications that arise with final salary schemes, unfunded Defined Benefit schemes, closed schemes and AVCs; and the value for divorce purposes of public sector pensions.

Scotland

The pension sharing rules in Scotland are a little different to the rest of the UK.

There are several key differences. In Scotland, only the value of the pensions that the couple have accumulated over the course of the marriage can be assessed i.e. anything relevant to before marriage, or following legal termination of the relationship, cannot be considered.

Scotland will allow a PSO to show a fixed monetary amount or a percentage (whereas England & Wales only allow a percentage to be used). Using a fixed monetary amount can provide greater certainty.